STORIES

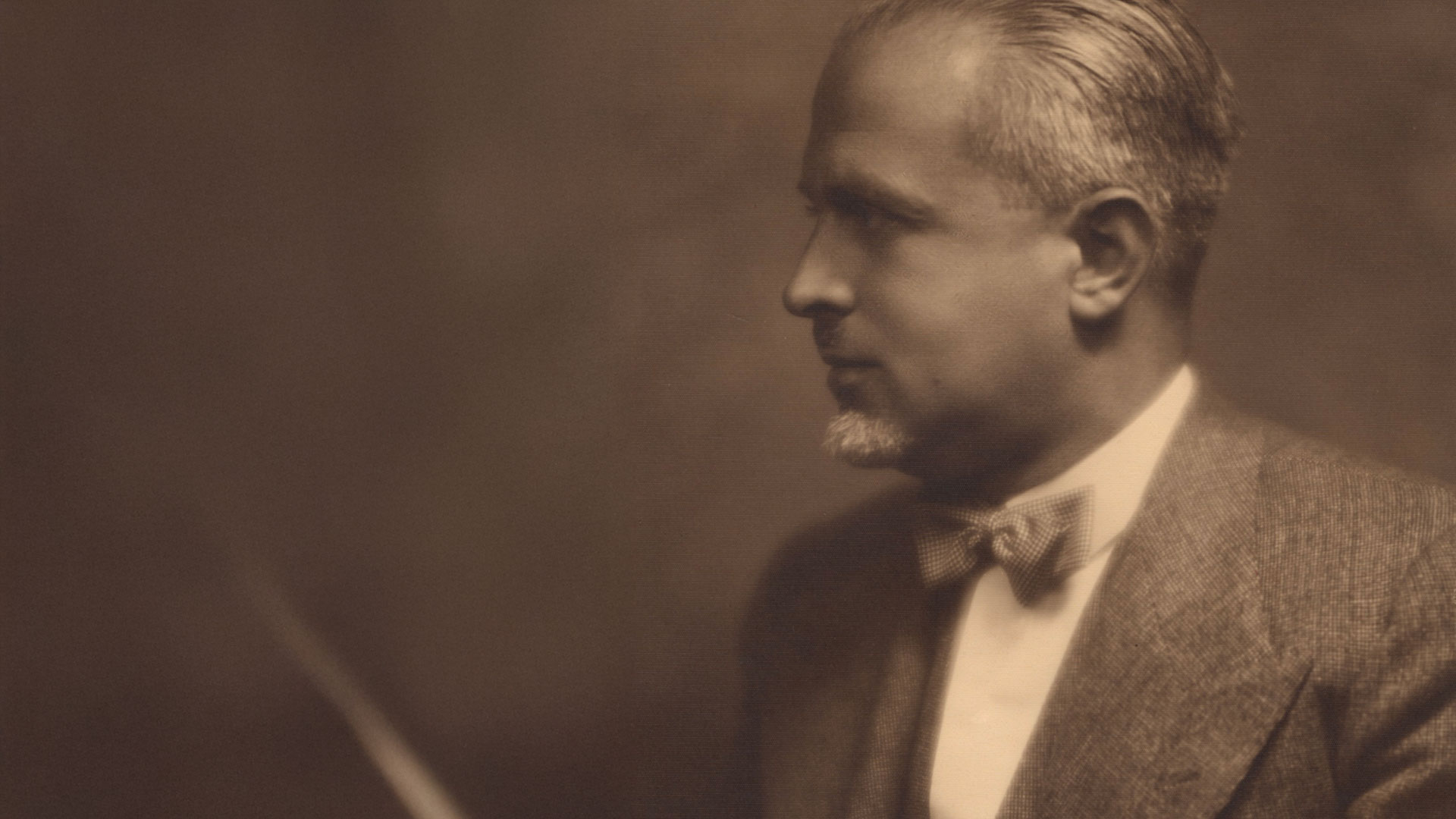

Piero Portaluppi:

architect and collector

Discover one of the most important Milanese architects of the first half of the 20th century and his great passion, the sundials.

Piero Portaluppiwas born in Milan in 1888. In 1910, he graduated in architecture, awarded the gold medal as the best graduate from the Polytechnic.

He began teaching at the University while starting his professional career.

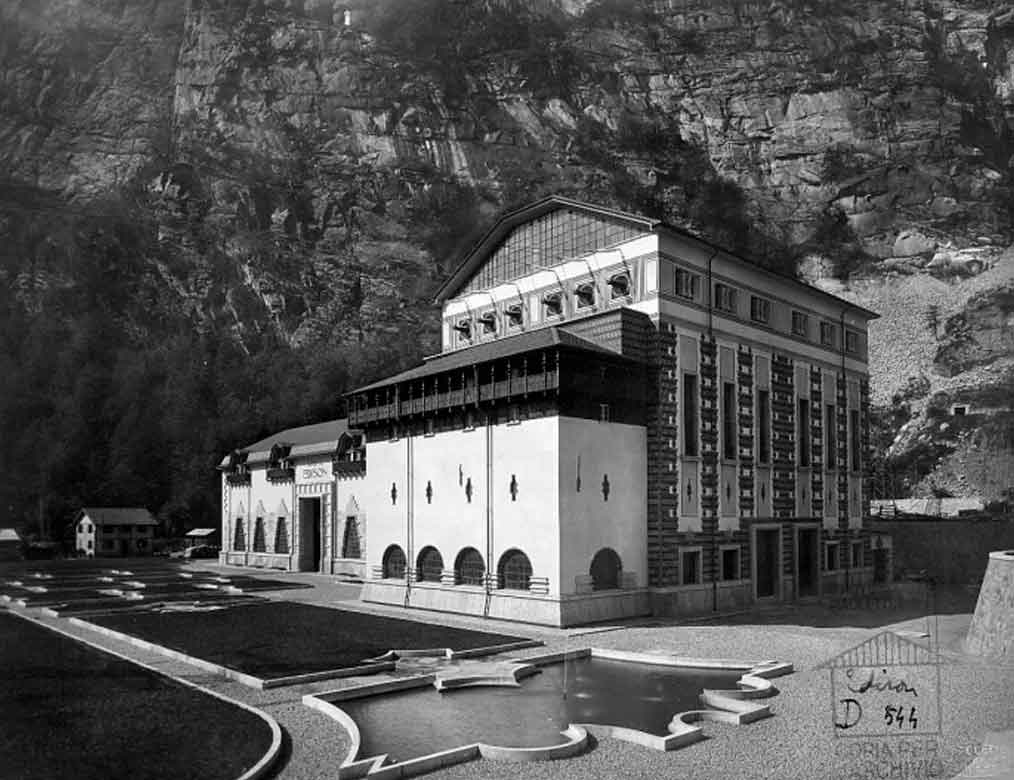

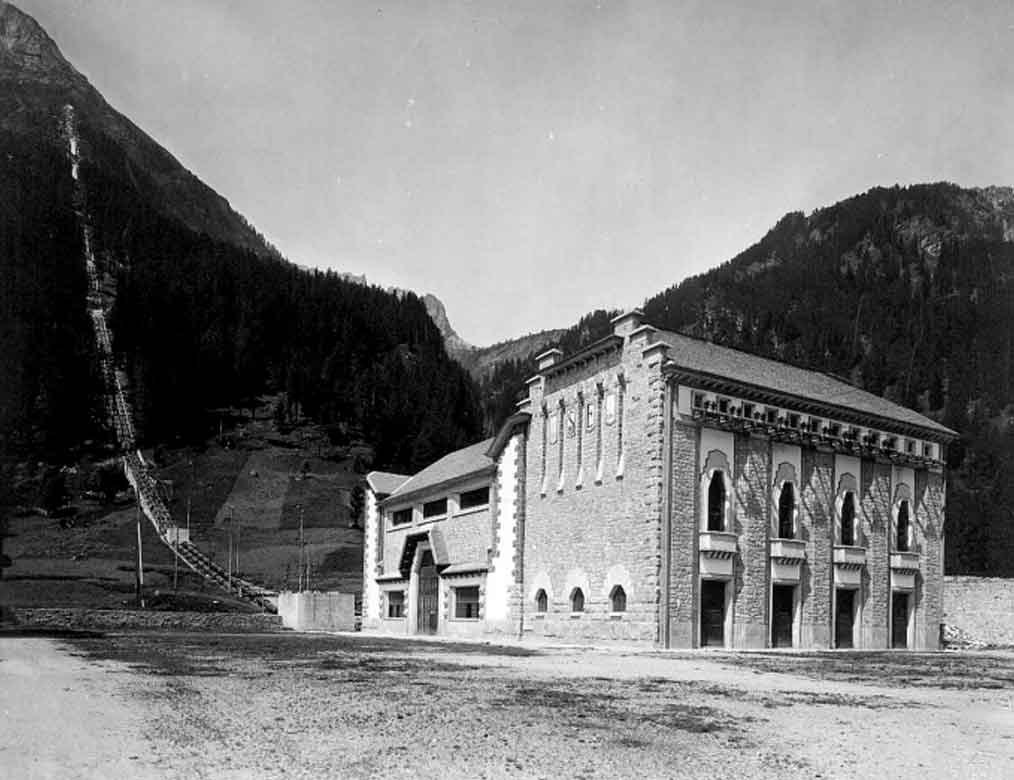

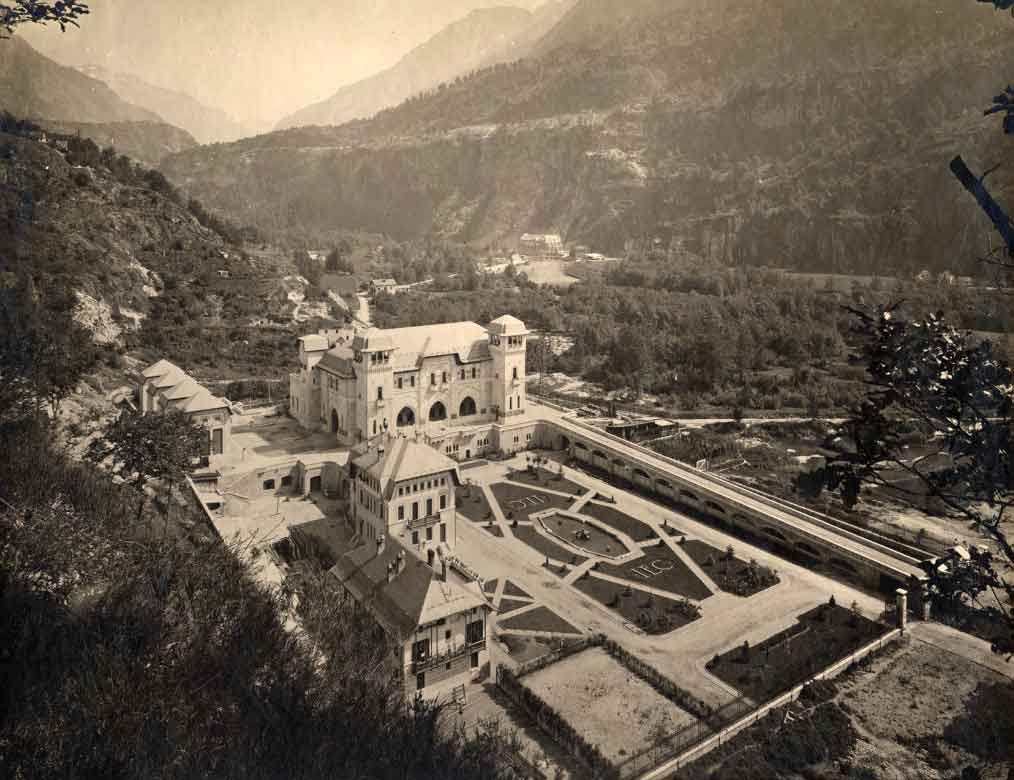

In 1912, he started collaborating with Ettore Conti, an entrepreneur in the Italian electric sector, designing many hydroelectric power plants, mostly in Val Formazza. The most famous ones in Crevalodossola, Verampio, Valdo, and Cadarese.

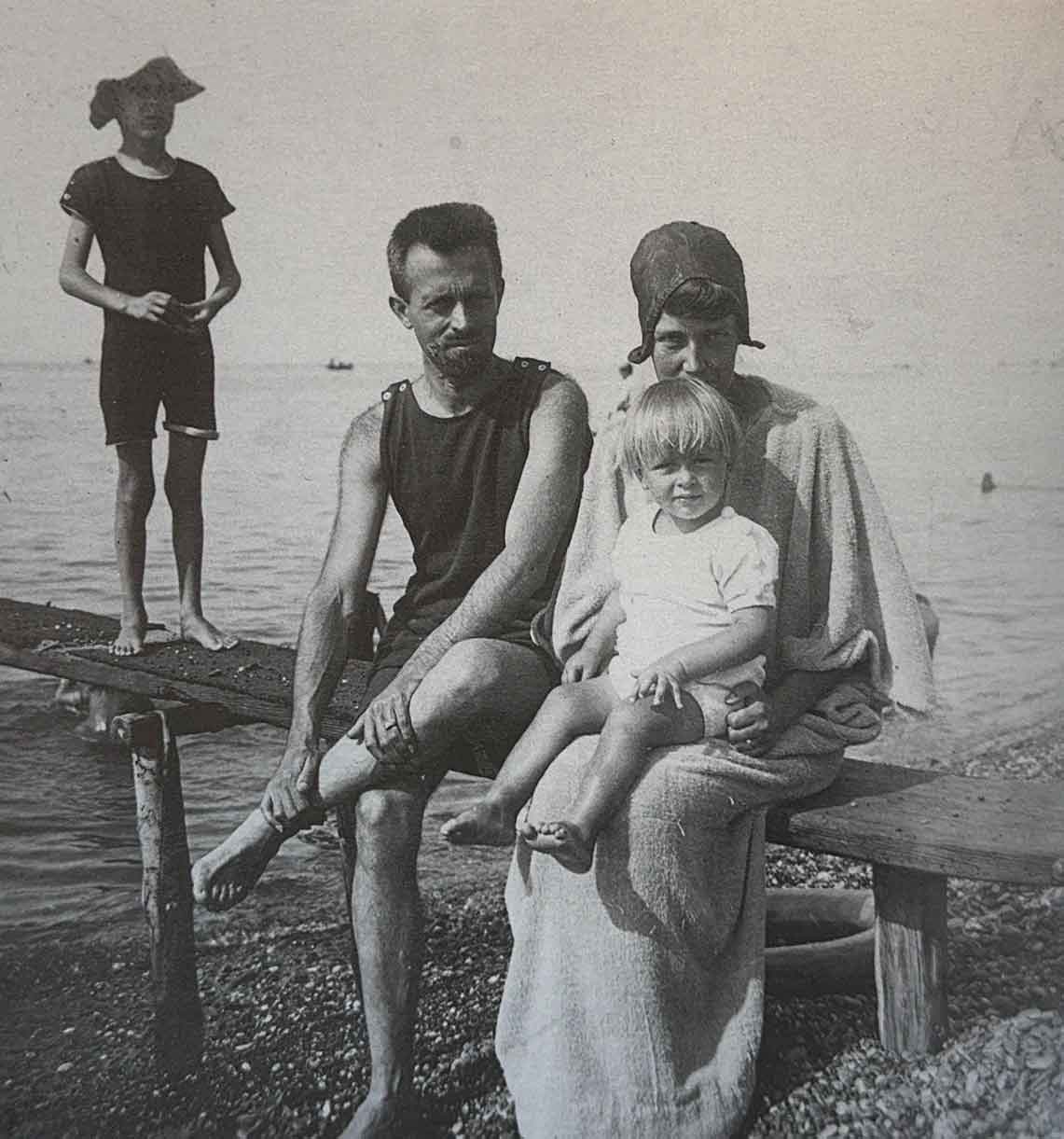

In 1913, he married Lia Baglia, the niece of Conti, with whom he had two children, Luisa in 1914 and Oreste in 1917.

At the end of the Great War, he resumed his work as an architect, creating significant projects, as the renovation of Pinacoteca di Brera, Casa degli Atellani in Corso Magenta -which would become his residence – Palazzo della Banca Commerciale Italiana, and Casa Crespi in Corso Venezia.

In the 1930s, his professional activity focused on a series of significant public and private projects, characterized by a moderately modernist style.

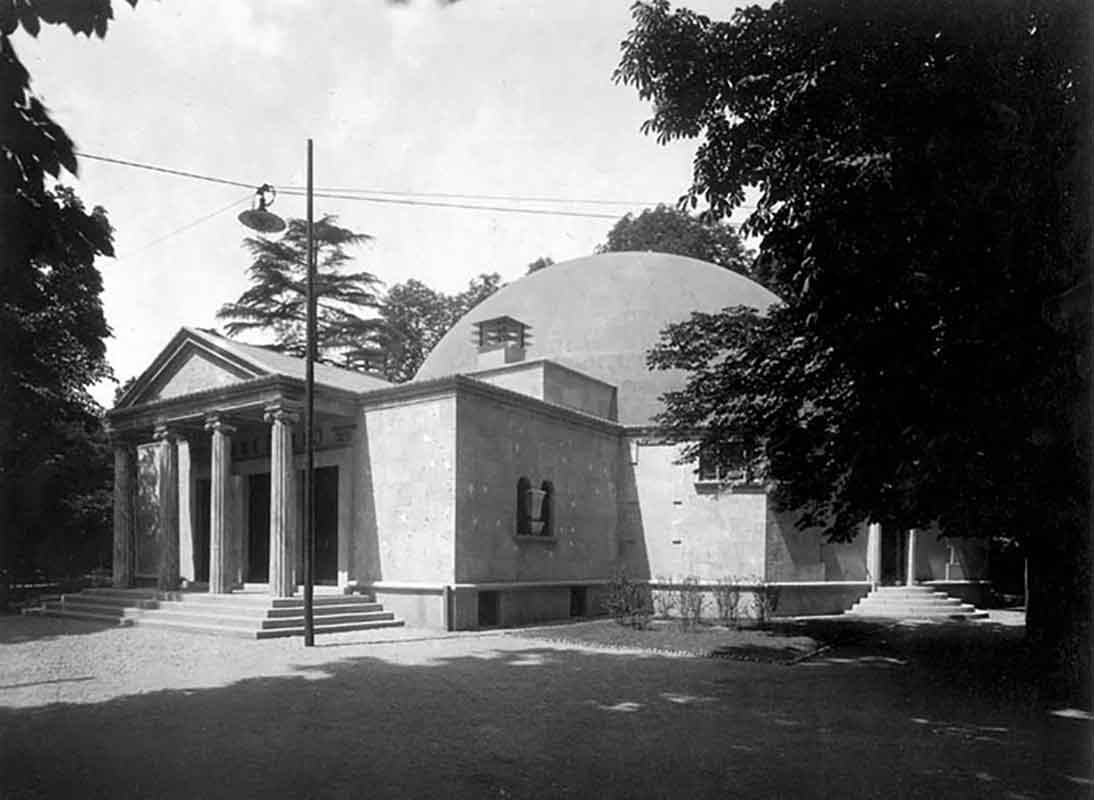

With his extraordinary creativity, Portaluppi left a lasting mark on his city, as in Villa Necchi Campiglio, the Arengario—now Museo del Novecento— the Hoepli Planetarium in the gardens of Porta Venezia, Casa Corbellini-Wassermann in Viale Lombardia, and last but not least Casa Radici-Di Stefano, which hosts a small treasure: the Boschi Di Stefano House-museum.

After World War 2, he continued his academic career and was involved in several major projects, such as the transformation of the Convent of San Vittore into the Museum of Science and Technology and the conversion of the Ospedale Maggiore into the Università Statale.

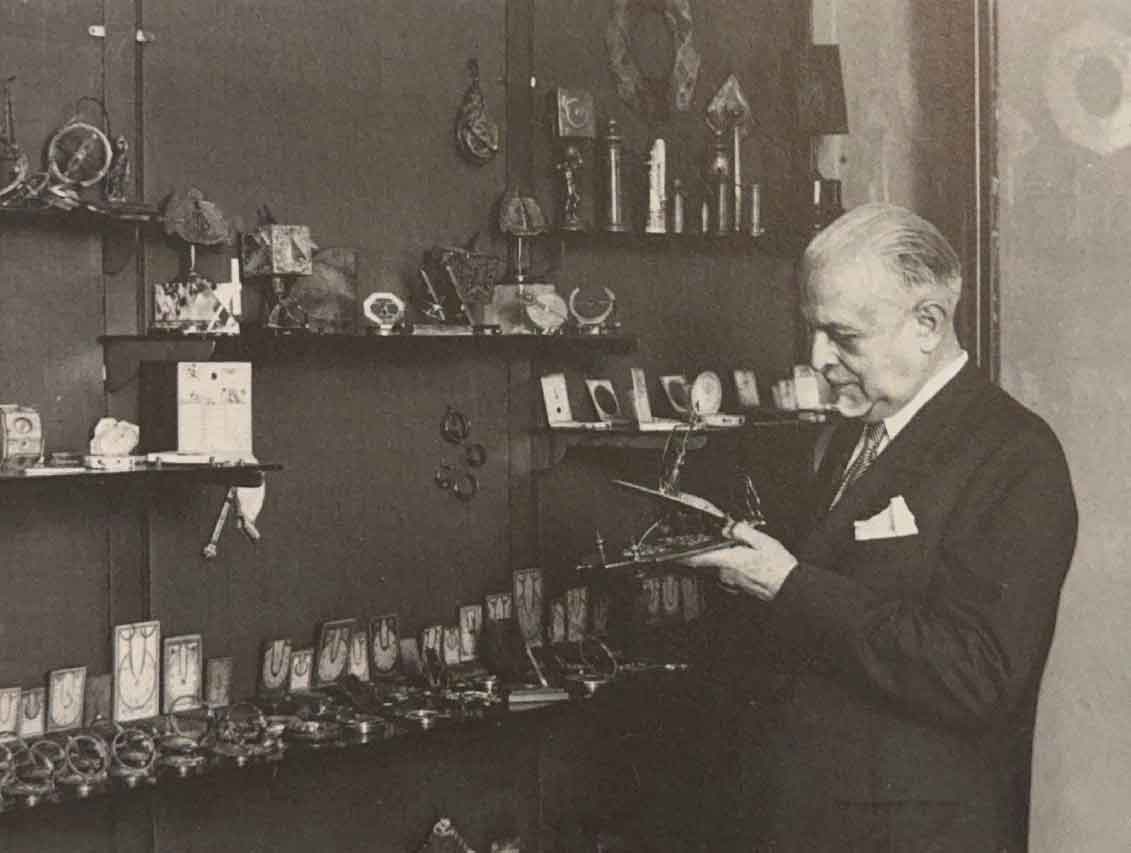

In his later years, he focused primarily on his great passion, the sundials, which he had been collecting since 1920.

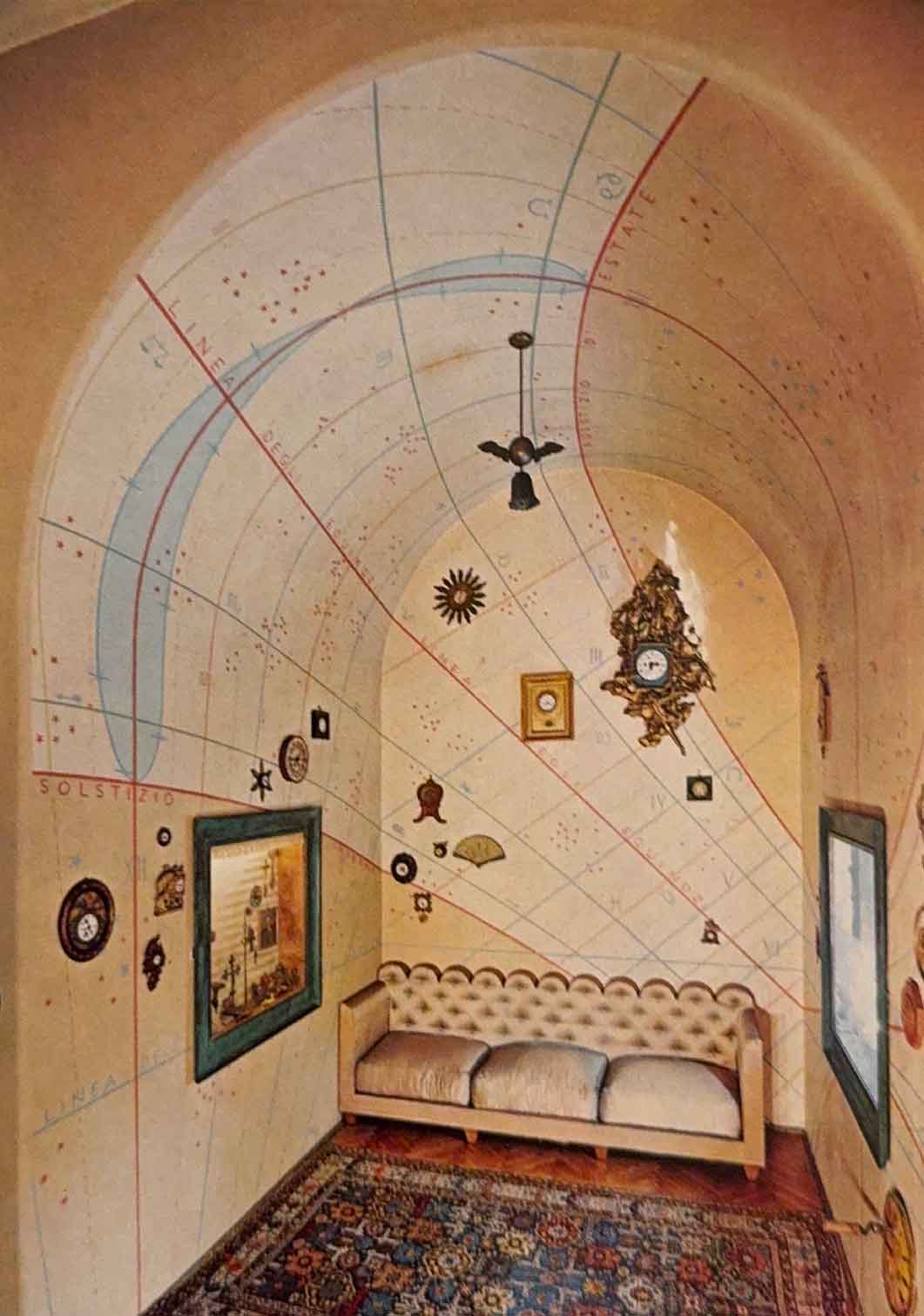

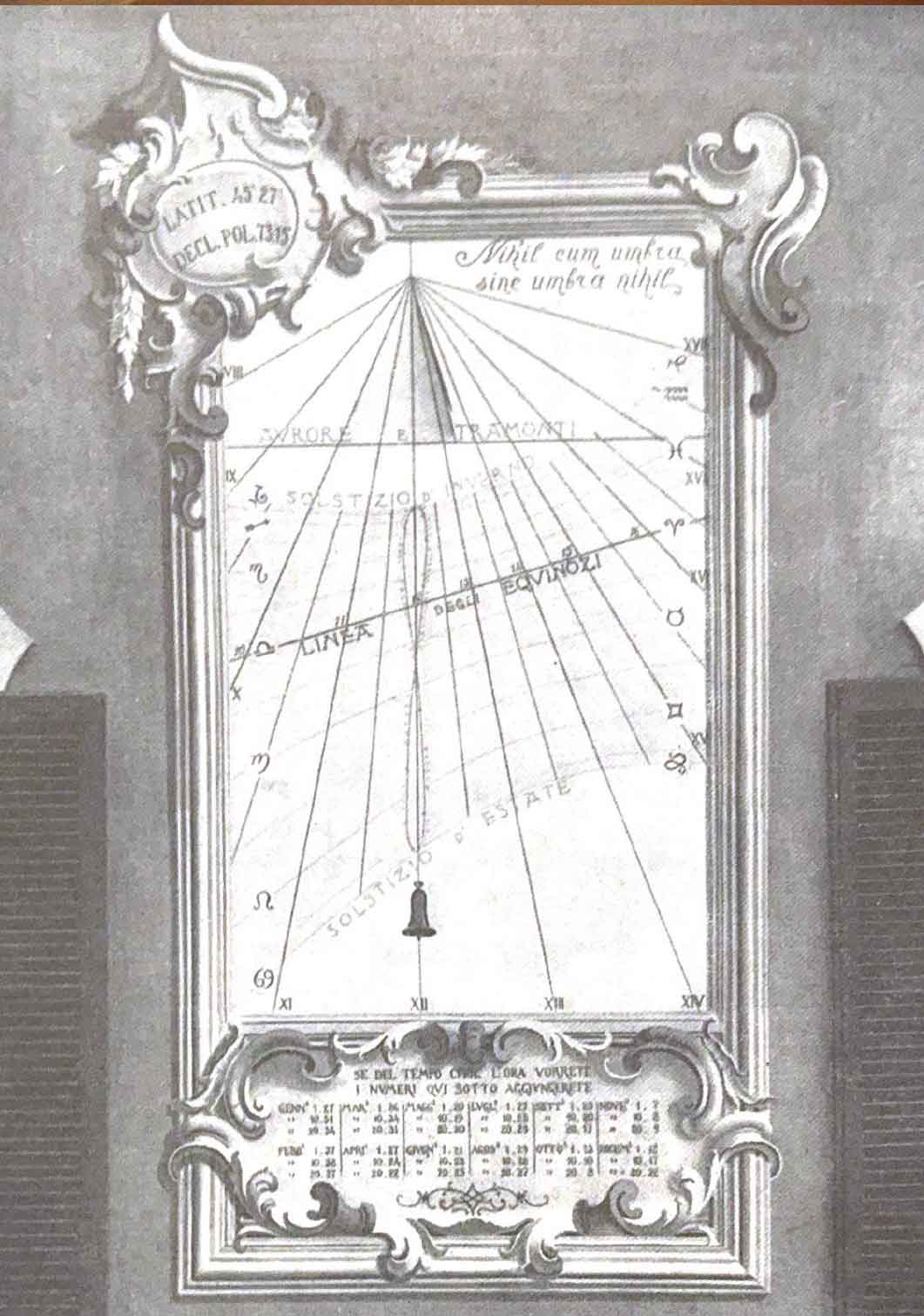

He himself built sundials on various buildings, including three at the Casa degli Atellani and one on the façade of Villa Necchi Campiglio.

He died in Milan in 1967.

In 1978, upon the death of her mother Lia, Luisa donated her father’s collection of sundials to the Poldi Pezzoli Museum.

The Sundial Collection

Sundials are instruments that indicate the time using a gnomon—an object that, when exposed to sunlight, casts a shadow on surfaces marked with lines corresponding to the hours of the day. Gnomonics is the science that studies the art of constructing such instruments and their use.

Sundials are very ancient devices. Already used by the Chaldeans, Egyptians, Babylonians, and Greeks, they became widespread in the Alexandrian and Roman world and continued to be used in later epochs. Small-size sundials were produced in large quantities and competed against mechanical clocks, which were more expensive and, until the late 17th century, less accurate.

The Portaluppi Collection consists of over two hundred pieces, dating from the 16th to the 19th century, which document the various types, functions, and evolution of these ancient time-measuring instruments, and many makers, some very well-known.

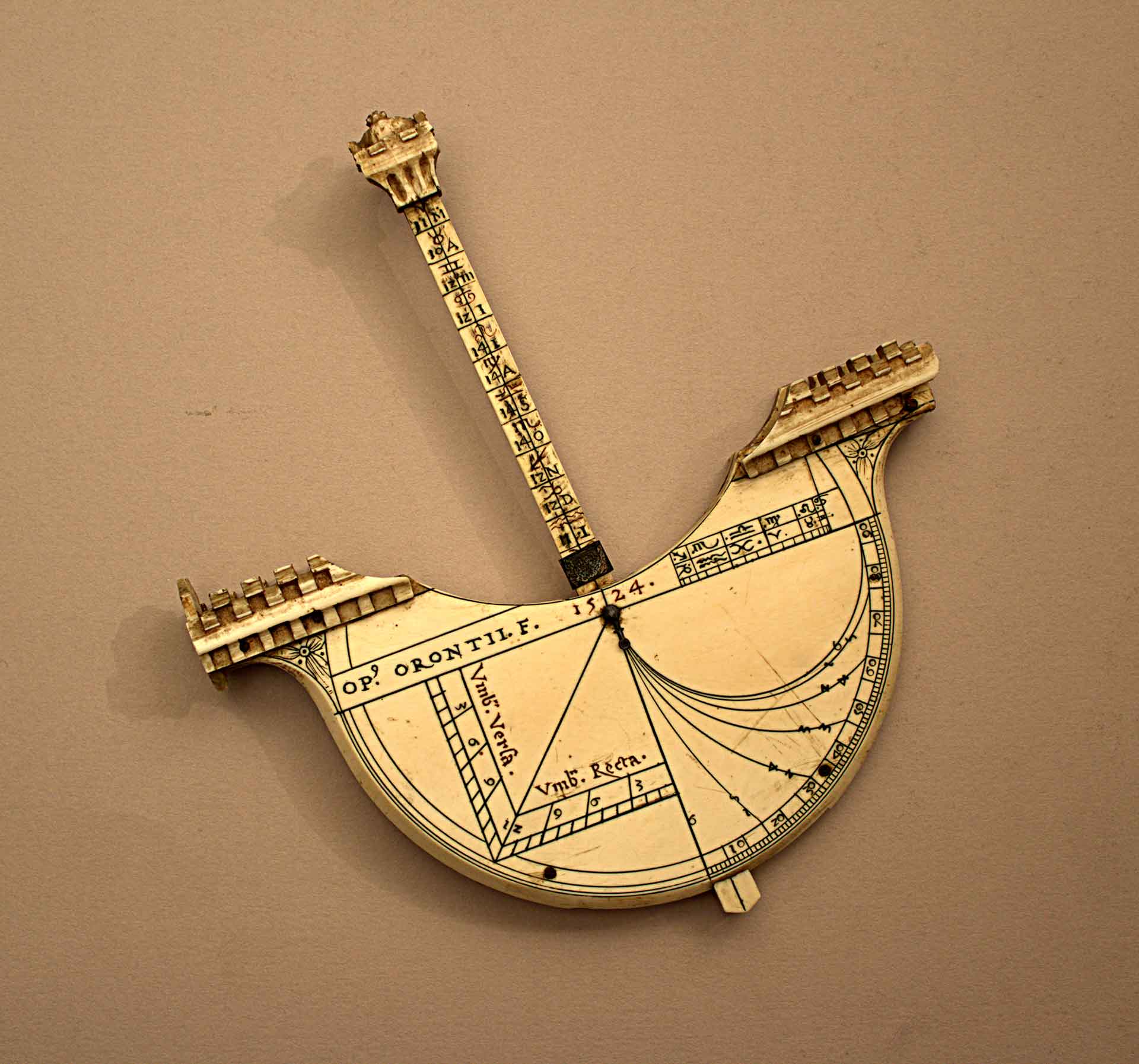

Among these extraordinary objects, stands out the Navicula de Venetiis.

Sundial called “Navicula de Venetiis”, Oronce Finé , 1524

It is the best known of the more than two hundred sundials collected by Piero Portaluppi and also one of the most important for its antiquity, preciousness of material and patronage. Made in 1524 by the famous French mathematician Oronce Fine, also the author of a literary work on sundials, it was intended for the court; in fact, it bears the emblems of King Francis I (a salamander and lilies).

The instrument functioned as a portable sundial: when the ship was properly oriented toward the sun a plumb line with a bead coming down from the mast cast its shadow on the dial. The hour track and two zodiac scales are engraved on the hull, while constellation signs appear along the mast. This is pivoted between the two tablets that make up the hull to be tilted according to the seasons. The name comes from the shape of the clock similar to a type of sailboat used in Venice.

The collection includes ring sundials, ivory diptychs, as well as those made of wood and printed paper; pillar dials and horizontal dials, as the silver Butterfield-type ones.