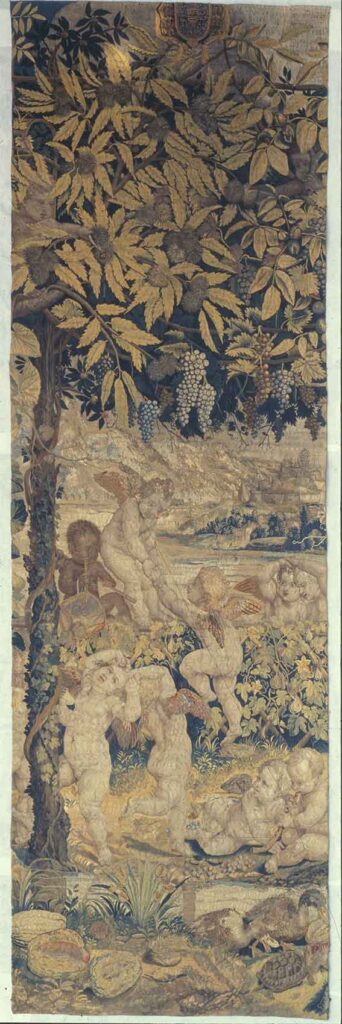

Tapestry with Playing Putti

Giulio Romano , 1540 - 1545

Description

Under an arbor with chestnut leaves and vine shoots play cupids: some climb a fig-covered espalier, others play flutes and drums while others dance. Prominent in the foreground beside a stream are gourds, ducks and a turtle. Visible at the top center is the cardinal’s coat of arms of Hercules II Gonzaga. This fragment is part of a famous cycle of tapestries called “Li Puttini” made in the Renaissance for the Gonzaga seigniory of Mantua. It is one of the pinnacles of Renaissance tapestry, thanks to the felicitous compositional invention of Giulio Romano and the faithful restitution of the expert craftsman Nicolas Karcher. In addition to the cloth now at the Poldi Pezzoli, the rest of the cycle consists of ten pieces and is divided between the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, Portugal, Compton Wynyates in England (collection of the Marquis of Northampton), and the Ducal Palace in Mantua. In 1539 the Flemish tapestry maker Nicolas Karcher had come to Mantua with his team of collaborators called by Duke Federico II Gonzaga (1500-1540), with the aim of starting a local tapestry manufactory, which started with the creation of this very cycle. Federico entrusted the design of the cycle to court artist Giulio Romano, a pupil of Raphael. The scene, cheerful and animated, faithfully draws on a Hellenistic iconographic source, the Εἰκόνες (Images) of Philostratus the Elder and in particular the chapter of the Erotes (cupids).

This source allowed the duke to celebrate good government, a new golden age that Mantua was experiencing thanks to the Gonzaga family: a time of peace and prosperity that had begun under Frederick II. At Frederick II’s death, the cycle had not ended, but was continued during the regency of his brother, Cardinal Ercole. A salient and original feature of the tapestries is the absence of a border, probably for the purpose of displaying them one in contact with the other in order to completely cover a room and give the viewer the illusion of sitting outdoors, in a tree-lined avenue, with river waters on either side and landscapes stretching to infinity. The compositional scheme repeats in each cloth a circular arbor occupying the upper part of the scene in which vine shoots are juxtaposed from time to time with other autumn fruits: pumpkins, pomegranates, chestnuts.

Above and within the plant racemes the cherubs are intent on harvesting grapes, gathering fruit, or hunting birds. The Milan fragment also features a delightful cupid with African features: this is one of the earliest evidences of the presence of colored pages at Italian courts, where they were prized for their beauty and exoticism. The compositional harmony is accentuated by a highly refined color palette, all played out in autumnal tones, in which yellows, ochres, and browns predominate, contrasting with the bright green and blue of the stream, while the landscapes fade into the distance. The brightness of the hues is skillfully enhanced by the presence of gold and silver yarns.

Exquisite is the study of shadows and reflections. No doubt the qualitative heights of these textiles are due to the presence of Giulio Romano, who directed and supervised the tonal choices. Finally, it is the perfect anatomical proportions of the infants, with their chubby cheeks and curly hair, that reveal to us the ancestry of these figures from the great Raphaelesque lesson. Frederick II died a few months after Karcher’s arrival in Mantua. The project was had completed by Frederick II’s brother, Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga (1505-1563), who had his own cardinal’s insignia added to the already completed cloths. However, the series had to be finished before 1545, when Karcher moved to Florence.

We know that the series originally consisted of “ten large cloths, two porters and two surcoats.” Remarkable was the cost of these artifacts: about 616 gold scudi in raw materials including Brussels wool and silk threads covered in gold and silver foil purchased in Milan were purchased to make it between 1540 and 1543. Karcher and his workshop were salaried weekly for three and a half years between 1541 and 1544. The tapestries are mentioned in Gonzaga inventories until 1707, when the dynasty died out. The Puttini disappeared from the documentary horizon until the late 19th century, when they re-emerged in Rome. Our fragment passed in 1878 from the Roman house of Don Carlo Cagnola to Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli.

Data Sheet

Author

Giulio Romano, 1499 ca. -1546

Date

1540 - 1545

Material and technique

wool; silk; silver threads; gold threads

Measures

341 cm x 107 cm

Acquisition

Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli bequest, 1879

Inventory number

0383

location

Fresco Room

The Fresco Room owes its name to the large ceiling fresco by Lombard painter Carlo Innocenzo Carloni, the Apotheosis of Bartolomeo Colleoni. The fresco, which comes from Villa Colleoni in Calusco d’Adda, was transferred to the Museum during postwar reconstruction work. On display in the showcase on the wall opposite the entrance is the magnificent Hunting Carpet, a unique example from northwestern Persia and dated 1542/1543. The room is also dedicated to hosting temporary exhibitions, lectures and conferences.

collection

Textiles

The heterogeneous textile collection includes important antique Persian carpets, Renaissance tapestries and 180 textiles dating from the 14th to the 18th century. Among them, rare Italian velvets and precious 15th century Lombard altar frontals. Antique Coptic textiles and Lombard and Flemish laces and embroideries, dating from the 18th and the 19th century, were acquired or received as donations.